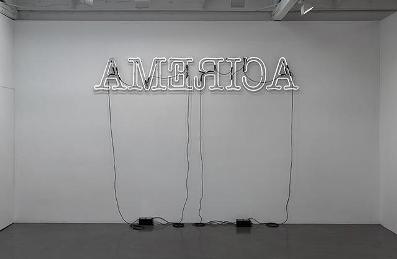

As mentioned in a past post, we are currently preparing to present online materials from LACMA’s archive for its landmark 1976 exhibition, Two Centuries of Black American Art. To accompany the primary exhibition materials that will be digitally accessible for the first time, we have developed related content to provide further art historical and institutional context for this historic exhibition. One feature I’m particularly excited about is the list of works by African American artists in LACMA’s permanent collection—and the fact that those publicly available in collections online can now be found on the landing page for American Art. Never before have visitors been able to go to one place to see the dynamic range of African American art in the collection—art produced over the course of more than 150 years in myriad artistic styles. The earliest work in the collection is Robert Duncanson’s striking still life of 1849 and the most recent is Glenn Ligon’s neon Rückenfigur made in 2009, which will be on view as part of Human Nature: Contemporary Art from the Collection, opening in BCAM on March 13.

It is amazing to be able to scroll through the images and encounter so many masterpieces, some of which are on view in the galleries—the online object record will tell you if a work is or is not “currently on public view.” From a curatorial perspective as well it is fascinating to see when works entered the museum’s permanent collection. (You can find this information by looking at the accession numbers—the first numbers that appear alone or after an initial letter(s) indicate the year the object entered the museum’s collection.) Some of my favorites happen to be historic acquisitions.

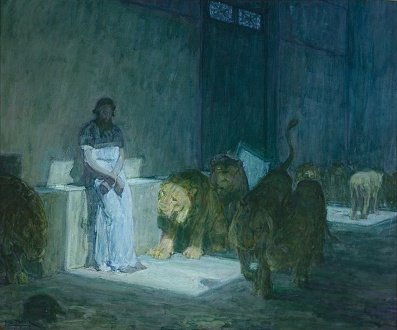

For instance, the first work by an African American artist that the museum ever acquired was Henry Ossawa Tanner’s Daniel in the Lion’s Den (22.6.3). Mr. and Mrs. William Harrison, whose collection formed the core of LACMA’s American art collection, purchased this beautiful and elegiac painting directly from the artist in 1918 and donated it to the museum in 1922. It has been one of the highlights of the American art collection ever since and is now on view.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Daniel in the Lions' Den, 1907-1918, Mr. and Mrs. William Preson Harrison Collection

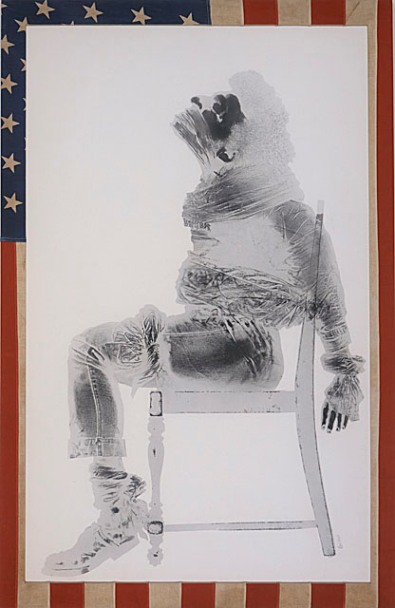

Other landmark acquisitions certainly include David Hammons’s Injustice Case (1970), which will also be on view in Human Nature. Hammons made this powerful work in response to the order by Judge Julius Hoffman to bound and gag Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale, who was a defendant in the 1969 trial of the Chicago 8, the group charged with conspiracy and inciting riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Hammons used his own body—covered with margarine and graphite and pressed against the paper framed with an actual American flag—to create this unique “body print.” The museum exhibited Injustice Case in its 1971 exhibition Three Graphic Artists: Charles White, Timothy Washington, David Hammons and purchased it with its acquisition fund through Brockman Muse Gallery, founded in Los Angeles in 1967 by brothers and artists Alonzo and Dale Davis.

Austen Bailly

Posted by lacma

Posted by lacma