We’re retiring our WordPress site, which was the home to Unframed since its inception in October 2008. We just launched the new Unframed over at unframed.lacma.org. Please redirect your RSS feeds to unframed.lacma.org/feed.

We’re retiring our WordPress site, which was the home to Unframed since its inception in October 2008. We just launched the new Unframed over at unframed.lacma.org. Please redirect your RSS feeds to unframed.lacma.org/feed.

We’re retiring our WordPress site, which was the home to Unframed since its inception in October 2008. We just launched the new Unframed over at unframed.lacma.org. Please redirect your RSS feeds to unframed.lacma.org/feed.

We’re retiring our WordPress site, which was the home to Unframed since its inception in October 2008. We just launched the new Unframed over at unframed.lacma.org. Please redirect your RSS feeds to unframed.lacma.org/feed.

Make a trip this Labor Day weekend to LACMA and squeeze every last drop out of summer before it’s gone! Friday evening Jazz at LACMA presents Janis Mann, known as a singer for her style and improvisational skills, at 6 pm. Tour the galleries for our latest displays, including the work of 29 abstract artists in Variations: Conversations in and around Abstract Painting and the final weeks of summer blockbuster Van Gogh to Kandinsky and the first retrospective of Southern California artist John Altoon. For more inspired and vibrant colors see Sam Doyle: The Mind’s Eye, which closes this Monday.

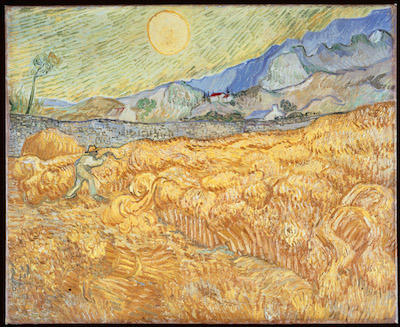

Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with Reaper (Harvest in Provence)

(Champ de blé avec moissonneur), 1889, Museum Folkwang. Photo Credit:

bpk, Berlin / Museum Folkwang/ Art Resource, NY

This season’s final Latin Sounds concert happens this Saturday at 5 pm, featuring Afro-Cuban pioneer Ricardo Lemvo for what is sure to be a performance full of energy and excitement. This outdoor event is free and open to the public, so invite friends and family! Take advantage of several free, docent-led tours throughout the weekend like the 50-minute walkthrough of our Latin American art galleries at 2 pm. At 1 pm, the Timekeeper Invention Club workshop takes place, but is accessible by a standby line only.

At the second-to-last weekend of the Torrance Art+Film Lab, join the fun at the Torrance YouTube Slam, a compilation of Torrance-area residents and LACMA staff picks from the video website, at 8 pm on Friday. The Instant Film Workshop on Saturday at noon shows you how to play the role of actor, cinematographer, and director to make your own movie. The lab ends its run on September 6.

Families are invited to Andell Family Sunday on Sunday at 12:30 pm to explore art and tech. Elsewhere, go on a tour of African Cosmos: Stellar Arts, LACMA’s latest African art entry, at 2:30 pm and take in the rich sounds of violinist Maia Jasper, cellist Marek Szpakiewicz, and pianist Nadia Shpachenko at Sundays Live at 6 pm in the Bing Theater. But the weekend doesn’t end there! Monday, check out Treasures from Korea for an expansive view at one of Korea’s most influential periods and Zuan: Japanese Design Books for more than 50 books and prints from Kyoto. Best yet, L.A. County residents get free general admission after 3 pm. Summer’s not over quite yet!

Roberto Ayala

Somebody, a new messaging service developed by filmmaker, artist, and writer Miranda July, debuts today. The app is a new way to communicate: rather than connecting directly with another person, Somebody helps mediate interaction by introducing a third party to the mix. It works like this: when a message is sent from person A to person B via Somebody, person A’s message is sent to person C, who then delivers it—in any way she wants, whether that be via verbal communication, performance, or an act of her own choosing—to person B. Created with support from Miu Miu, Somebody is available for free in the iTunes Store.

LACMA is one of the official hotspots for Somebody. (Other hotspots include the New Museum, New York; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; Portland Institute of Contemporary Art; Boston Museum of Fine Art; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; and Museo Jumex, Mexico City.) At the intersection of many elements that make up a large metropolis—major modes of public transportation, streets/intersections, business centers, and individual perspectives—LACMA serves as a fitting hub for spontaneous interaction and experiences through Somebody. LACMA chatted with July about the app and how she imagines it will be used. Miranda July will be at LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab on Thursday, September 11, to talk more about Somebody.

LACMA: How did you come up with the concept for project? What came first, the idea, the film, the app, or did they all intersect at once?

Miranda July: I had the idea for the app about three weeks before Miu Miu contacted me about making a short movie. It was originally called “Proxy”—I think every app is called Proxy to begin with. The idea really electrified me; I felt oddly determined to make it, even though barely know what an app is and certainly didn’t have the money lying around to pay for it. When the invitation came from Miu Miu I didn’t immediately connect it to the app—I just thought it would be a good way to get my head back in to directing after writing a novel for the last few years. My first idea was something about adults giving birth to other adults. My husband’s reaction to that idea was, “Hmmm, you should do something more democratic—like your We Think Alone project.” I said harumph and went to brush my teeth. Five minutes later I had it all worked out: the movie about the app, pitching the actual app to Miu Miu. I emailed the idea the next day to Miuccia Prada and her right-hand woman, Verde Visconti, and they completely got it immediately. And they respected that the app was mine, that they were supporting my work in this very organic way. The movie I wrote created a world for both the Miu Miu clothes and the app, it all felt very natural. That was in April I think—so I’ve spent the last five months making the app and movie simultaneously.

LACMA: How has the evolution of your work been informed by developments in technology?

MJ: I never mean to make work about or with technology, it just keeps happening—probably a lot of artists and writers can say the same. I’m old enough to feel the newness and strangeness of the technology, but no so old as to be able to see outside it clearly. So it’s interesting, like a dream I can’t wake up from, like “When’s life going to get back to normal like it was when I was a kid?” I also feel some kind of responsibility to poke back at this stuff that so completely impacts every second of my life.

LACMA: What’s the significance of the hotspots, and how might the location inform how the app is used? Why did you pick cultural institutions to be the hotspots?

MJ: From the start I knew it would be almost impossible to get enough users for Somebody to really work the way it does in the movie—with strangers delivering messages on the street and in restaurants. I mean it might work like that eventually in like one block in Silver Lake or in Portland, but mostly I think friends will use it amongst each other, at parties, colleges, workplaces. The way to make it work in public was obviously to go to where the people already are gathered. Initially I was focused on festivals and concerts—sporting events! Then I realized museums made more sense because they are already focused on inviting an engaged audience inside; this is an ongoing part of their job. Somebody fit very easily in to conversations curators were already having about interactive art, digital art, performance.

LACMA: We’re in Los Angeles, so we have to ask, can you imagine someone being “discovered” by this app?

MJ: Sure. Even though Somebody is designed to create fleeting, undocumented experiences in real life, I imagine people (myself included) will be tempted to video message deliveries. So it is likely that there will be many little scripted performances popping up online—written by one person and performed by another. Someone could be discovered for either their writing or their incredible performance. But there are already so many ways to be discovered, Somebody is probably better for something else.

LACMA: Tell us an imagined scenario that would take place at LACMA and mediated by the Somebody app.

MJ: Well, the nice thing is you don’t have to raise your hand in public or do anything that calls attention to yourself—so if a museumgoer wants to use Somebody, she might quietly write a message to her friend, who is right there beside her, and covertly choose a stand-in to deliver it. Then, with any luck, a few minutes later a stranger will walk up to her friend and perform . . . a confession of love? Or these friends might be feeling daring and start browsing the “floating messages” to look for one nearby. They see a message that asks them to buy someone a cup of coffee (you can add actions to your messages). They accept the mission and find the recipient and buy him a cup of coffee and he ends up becoming part of their polyamorous lifestyle. Or just enjoys the surprise and the cup of coffee—the message was from his wife in Atlanta who misses him.

I remember visiting the Picasso Museum in Barcelona and being fascinated by one of Picasso’s school text books on display. I can’t remember the textbook’s subject because that part was irrelevant. My fascination lay in what had been drawn in the margins. I imagined a young Picasso bored by his teacher and distracted by a clearly more pressing issue as you could see pencil marks erased, redrawn, and drawn again. He was trying to get the right angle, shape, and musculature on the arm of a figure he was drawing.

Looking at artists’ sketchbooks can offer an intimate glimpse to their process, obsessions, struggles and daily life. At LACMA, students often use and make sketchbooks to record their observations, ideas, and reflections. I spoke with LACMA teaching artist George Evans, who has hundreds of sketchbooks, about his lifelong relationship with this mobile medium.

Karen Satzman: You often teach our teen Sketchbook class. Tell me about your first sketchbook.

George Evans: My first sketchbook came from my dad— I took his! My dad was a sign painter. He could draw. I had my first sketchbooks in junior high. In high school, I studied with Bill Tara and Bill Pajaud at Tutor Arts. (The Tutor Arts Program was founded by artists Bill Tara, Bill Pajaud, and Charles White.) Every Saturday we had to have five drawings; it set a standard. We were told “your sketchbook is your studio,” and that clicked for me. As long as you have a sketchbook, you can work anywhere, on the bus, in the park. I would come to LACMA and Barnsdall to draw from the collection and in the park. Submitting my sketchbook with my Cal Arts application played a big part in getting a scholarship.

I still see Bill Pajaud, and he still has his sketchbooks from the 1950s, when he was at Chouinard (now known as Cal Arts). When I see him I always bring my sketchbook to show him what I’m working on. We still have that kind of relationship.

KS: What is the role of the sketchbook for you?

GE: Keeps me thinking . . . I find a lot of answers there. I have sketchbooks everywhere: in the car, on the bedside table. I’d be on the freeway stuck in traffic and an idea would come to me. I’d quickly create a thumbnail. You always have something to work with. I sketch in bed. I start with a pen, then add a little water color. At 2 am, my wife would wake up ! [Evans laughs and shakes his head.]

My sketchbooks have followed me all of my life. Keep myself growing and document my ideas. A sketchbook is a passport. Part of my sanity. You can express yourself fully. It is your prerogative to share or not.

KS: Do you share yours or keep them private?

GE: Well, I just showed you mine!

KS: True! So, how many do you have?

GE: Hundreds! Some are damaged. They go all the way back to high school. I lost the ones from junior high. And, I just got an iPad. I use the Procreate app. I am experimenting with observational drawing. It is a different tool. It does things differently, makes me curious to look at things differently.

KS: Where do you keep your sketchbooks?

GE: Wherever I can. The old ones are in plastic tubs. Ones from the last 10 years are in the house on bookshelves.

KS: Tell me about teaching.

GE: I use a lot of the same ideas I was taught with at Tutor Arts. They would say. “Draw in your room, draw the clothes in your closet.” You are studying drapery, see? This is how it works.

No erasers! I have them work in pen. It is a commitment. Learn to work with your mistakes. At Tutor Arts we drew with sticks and ink. Unconventional methods make you see things differently.

KS: What can we learn by looking at an artist’s sketchbook?

GE: I’ll never forget looking at one of Marc Chagall’s sketchbooks—there was one drawing, just after his baby was born. It looked like a cabin, with a baby at the table, food at the table. Shows how the artist captures simple, everyday life. Different from photography; things a photo can’t say, a sketch can.

George Evans next Sketchbook class at LACMA is designed for teens. Small and portable, sketchbooks are a perfect discovery for this on-the-go group! Class starts on Saturday, September 13. For more information or to enroll, call the Ticket Office at 323 857-6010 or click here.

Karen Satzman, Director, Youth and Family Programs

Kimono for a Modern Age, currently on view in the Pavilion for Japanese Art, showcases how kimono designs evolved to integrate traditional and modern patterns with new chemical dyes and textile techniques during the first half of the 20th century. As a summer intern in LACMA’s Conservation Center, I had the privilege of walking through the show with Catherine McLean, the head of Conservation in the Textiles Department.

Woman’s Kimono with Geometric Pattern, Japan, early Shōwa period (1926–89), c. 1940, Costume Council Fund, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Walking through the exhibit, I was captivated by the pristine and natural display of each costume. The kimonos hang delicately with their arms straight out and the material extended flat on the surface of each wall. The fabric of the kimonos appear entirely smooth and wrinkle free, allowing viewers the opportunity to appreciate the beauty of each patterned design.

As I began talking to McLean, however, I soon learned the appearance of effortless perfection had not been the case behind the scenes. McLean explained that while the garments now seem smooth and crisp, it had not been easy to make them look that way.

The textiles conservation team had struggled to find a way to properly store the kimonos, especially given the fact that LACMA has substantial holdings of the traditional garments. At first, McLean explained that the Costume and Textiles Department tried to store the kimonos using a Western technique. In conservation practices in the West, conservators usually attempt to eliminate sharp creases so that the materials do not wear down along folds. In an attempt to adhere to this method, McLean and her team lined the folds of each kimono with long cotton pads and tried to fold the material as few times as possible.

This method took up a significant amount of time and space. What’s more, when the conservators took the kimonos out of storage, they found that they had become rumpled and wrinkled.

Thus, after years of storing the kimonos in the Western style, McLean, the team in the Conservation Center, and Sharon Takeda, senior curator and department head of Costume and Textiles, decided that they would draw instead from centuries of Japanese ritual and culture and begin folding the kimonos in the traditional style. In contrast to conventional conservation methods, the Japanese actually welcome creases as a sign of proper folding. There is a very precise way of folding and storing kimonos in Japan. There are even specifications about which arm should be folded over the other. (Left over right means that the kimono’s owner is alive, and right over left means she is dead.) In order to get all the details right, McLean asked Rika Hiro of the Conservation Center to teach an informal class to McLean and her team on how to fold LACMA’s kimono collection in the traditional style.

The traditional method of folding kept the kimonos from wrinkling in unwanted places and allowed them to be stored in a compact, transportable manner. In fact, after using the traditional method to fold the material, all 35 kimonos in the current exhibit fit into just three flat boxes.

Looking back, McLean isn’t surprised that the department ended up using traditional methods to store the kimonos. The Japanese have been wearing and storing kimonos for centuries, but modern conservation techniques were only truly formalized in the past several decades. Sometimes, it turns out, it makes more sense to learn from the cultures that we are trying to preserve.