Tonight, Grammy-nominated vocalist Denise Donatelli performs for Jazz at LACMA, our free weekly outdoor concert series. You can hear songs from her latest album, When Lights are Low, at her website. Enjoy a drink at Stark Bar, a dinner at Ray’s, or just soak up the atmosphere of the museum campus while Donatelli performs. Don’t forget—admission to the galleries is also free (for L.A. County residents) after 5 pm.

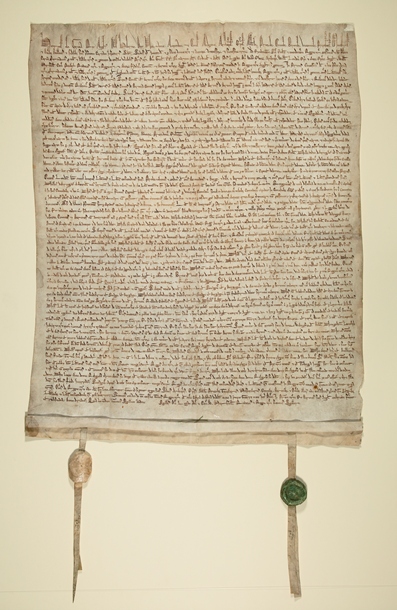

As mentioned earlier this week, an original Magna Carta from the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, is on view for a very limited time in the Art of the Americas Building. It went on view on Tuesday and is coming down this Thursday, so this is your only weekend to come see this historic document. Be sure to check out our other exhibitions on view while you’re here.

Tomorrow night, as part of BritWeek, we are premiering the documentary Beyond Time: William Turnbull, which looks at the life and work of this influential sculptor and painter. Filmmakers Alex Turnbull (William’s son) and Pete Stern will be here in person for a Q&A following the screening. Here’s a look:

Starting this weekend our free Andell Family Sundays will take on a new theme, “Build It!” Show your kids some of the furniture on view in our galleries—whether from Korea, Europe, the U.S., or elsewhere—and then take part in art-making activities together to build your own mini-furniture.

On Sunday evening the Young Musicians Foundation Chamber Ensembles will perform works by Beethoven, Brahms, Dvorák, and others during our ongoing Sundays Live free concert series.

Scott Tennent

Posted by lacma

Posted by lacma