Stanley Kubrick closes this Sunday. If you have yet to experience it, reserve tickets before this expansive, special exhibition ships out. If you have seen it, come back for seconds! You’ll be surprised how much more Stanley Kubrick has to offer on return visits. Delve once more into the mind of one of the greatest visionaries in modern film this final weekend in the exhibition and in the Bing Theater.

Kubrick and Co.’s closing act presents Full Metal Jacket with China Gate on Friday night and Eyes Wide Shut after Belle de Jour on Saturday night. The first evening features stories of desperate camaraderies, born in jarring Pacific war theaters. The second evening centers on the fates of curious lovers, their infidelities, and their fantasies. Make reservations posthaste–this is your last and best shot to see two of Kubrick’s classics on the big screen. On Saturday, make a night of it and dine with executive chef Jason Fullilove and his RED Dinner series, a specially themed four-course prixe fixe meal. This time around, plates like “Spartacus” with pork duo, loin & cheek, fennel puree, chanterelles, and Persian shelling beans are inspired by all of Kubrick’s masterworks. For reservations, call 323 377-2698 or email red@patinagroup.com.

Musically, fans of (free) jazz, Latin, and classical music will have their hands full this weekend. Friday night, at Jazz at LACMA, vocalist and songwriter Inga Swearingen graces the stage in front of Urban Light; Freddie Ravel and his rhythmic keyboards light up Hancock Park (behind the museum) for Latin Sounds; and Sundays Live on Sunday features the Capitol Ensemble performing Johann Wenzel Kalliwoda and Johannes Brahms.

For families, visit the museum on Saturday morning for a free Family Tour, meeting at the BP Grand Entrance. Andell Family Sundays on Sunday afternoon shares workshops and activities based around the theme “Architecture is Art.” In neighboring Redlands, the LACMA9 Art + Film Lab hosts two films, Steamboat Bill Jr. and El Norte, on Friday and Saturday nights, respectively, along with a free Mini Documentary film workshop where you get to tell the story of a person or place yourself and a free Soundscapes workshop. This is the second to last weekend of the LACMA9 Art + Film Lab in Redlands before it roves over San Bernardino on July 26.

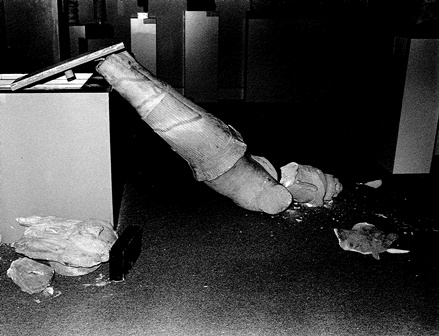

Pinaree Sanpitak, Hanging by a Thread, 2012, Courtesy of the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art, New York. Installation views, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2013 © Pinaree Sanpitak. LACMA/Museum Associates 2013

Around the museum visit the Pavilion for Japanese Art to see the notorious Red Fuji and The Great Wave by Katsushika Hokusai in Japanese Prints: Hokusai at LACMA, entering its last month in Los Angeles. Recently opened in the Ahmanson Building, Pinaree Sanpitak: Hanging by a Thread, Bangkok-based artist Pinaree Sanpitak displays eighteen hammocks woven from printed cotton textiles conveying the solace she experienced after the devastating 2011 floods in Thailand. On the west side of campus see Peter Zumthor’s vision for the future of LACMA in The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA and the buzzworthy James Turrell: A Retrospective.

Roberto Ayala

Posted by lacma

Posted by lacma